Photos by Ivica Ivčević

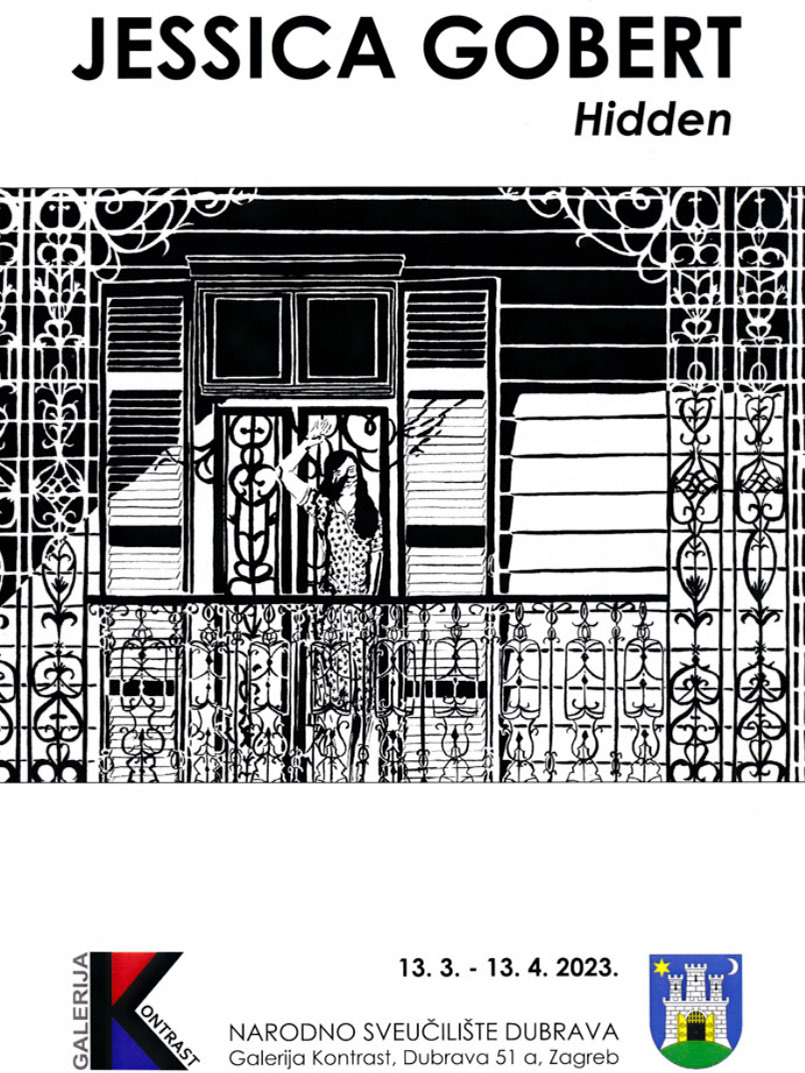

In Shadows of Intrigue, the artist, Jessica Gobert, beckons the audience into an ink noir universe. Through a slow, painstaking process she has covered the respective 2m and 1m70 long paintings with her paintbrushes and black ink. Her details cover the 5 large formats, as well as 25 crosshatched smaller works, and invite the viewer to lean in close.

The collection, heavily inspired by noir-films, form a loose narrative around a murder being committed. Through hints and red herrings the paintings asks more questions than they answer and leave the viewer to decide for himself.

The 25 small crosshatched formats are set to pave the way, bewilder, confuse and narrate the happenings. Serving almost as a cinematographic device, they serve as zoom-ins and are a tool to invite the viewer to find the details in each painting. This visual contrast between macro and micro gives us a sense of solving a puzzle, inviting us into a visual game.

While walking the grounds of this English Manor House where the story is set, and gazing at the walls, one might uncover a myriad of references. One might find the railing of the 1950 Billy Wilder film, Sunset Boulevard, the framing and composition with the statue of Hitchcocks Notorious, the faithful and yet ominous dog from Rebecca, Jasper. It is a love letter to noir, gothic films, to end of the 18th century paintings (with references to Rupert Bunny’s Fresca, 1921 for example).

Going beyond the visual language of the noir film, the exhibition follows the classic storyline of the genre. It especially follows the way women are classified and portrayed. From the spider woman who weaves her web and traps men, who lives in the underworld and only comes out at night, to the innocent wife, childlike and almost asexual. It is an exploration of women’s portrayals, their role, from passive and decorative to deadly.

Through framing and composition, the paintings show the struggle between dominating and dominated, retelling a classic story which is culturally imbedded in all of us. Do we notice how the frame manipulates us? Do we believe the male narrative whilst the visual tells us a different one (as can be heard throughout the 1944 film Double indemnity by Billy Wilder)? Is it a question of point of view or of fact? Is that regret, grief or a vengeful expression on the woman’s face?

The artist uses film noir codes in her drawings, such as in the painting The make-up table which pictures a woman gazing at herself in the mirror (a sign of duplicity in the genre as seen in The Big Heat by Fritz Lang, 1953), the reflection representing her “true face” as she ignores the man behind her. As Janey Place writes in her essay Women in Film noir, “Self-interest over devotion to a man is often the original sin of the film noir woman”.

The question of motive is never shown or even directly asked, the narrative relying instead on the surroundings, notes, flowers, patterns. Even the murder (as can be seen in the painting of the same name), seems almost too polite, with the murderer in the background brandishing a gun one has to bend over to notice. The paintings are seemingly innocent, but if observed closely, lead to hidden depths.